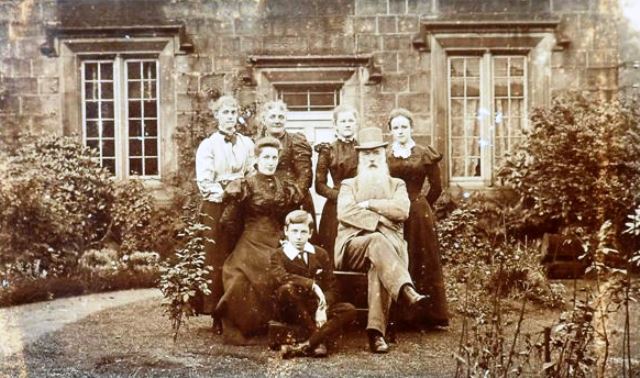

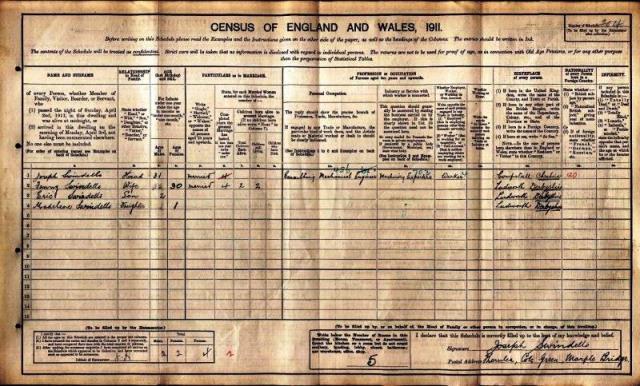

Mrs Joseph Swindells

Note: Mrs. Joseph Swindells, who died in 1965 at the age of 86, was Miss Fanny Thornley when she taught at Compstall School. She was a native of Compstall and lived in the district all her life. Her family were closely connected with Compstall Mill.

Scholar's Walk, Whit Friday. *Eton suit worn by Woodmass boy? (right in photo)

Photograph shows the headmaster, of Compstall School, and his family and Miss Thornley (later Mrs Swindells), far right, back row.

Memories of Compstall

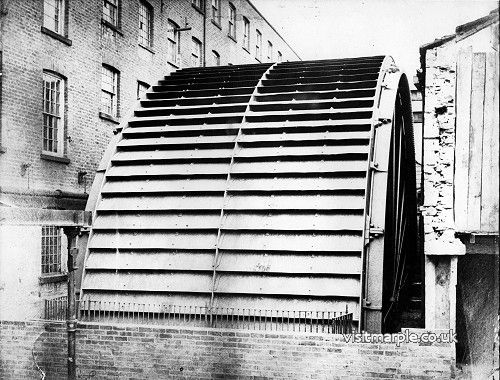

The Lily waterwheelIn the early part of the last century George Andrew and sons founded and built the village of Compstall. George Andrew himself worked as a workman, travelling, with his meals tied up in a red cotton handkerchief slung over his shoulder. He first of all built Compstall Bridge over the river Etherow, the mill and printworks adjacent to the river which provided a good supply of suitable water. He built two mill lodges which fed the famous water wheel named The Lily, very well known. Then he built cottages, St. Paul’s church and Sunday School, used as a day school as well for a few years, the Athenaeum, with its gallery, for social events, a reading room, church houses whose foundations later provided a post office, a band pavilion, founded and maintained a local brass band, made a cricket ground, founded a club and helped to maintain it, built two halls, Greenhill, afterwards called Compstall Hall, and Ernocroft Hall, one each for his two sons, George and Charles. They in turn married, Charles to live at Greenhill, George at Ernocroft Hall. They each had six daughters, never a son to carry on the name.

The Lily waterwheelIn the early part of the last century George Andrew and sons founded and built the village of Compstall. George Andrew himself worked as a workman, travelling, with his meals tied up in a red cotton handkerchief slung over his shoulder. He first of all built Compstall Bridge over the river Etherow, the mill and printworks adjacent to the river which provided a good supply of suitable water. He built two mill lodges which fed the famous water wheel named The Lily, very well known. Then he built cottages, St. Paul’s church and Sunday School, used as a day school as well for a few years, the Athenaeum, with its gallery, for social events, a reading room, church houses whose foundations later provided a post office, a band pavilion, founded and maintained a local brass band, made a cricket ground, founded a club and helped to maintain it, built two halls, Greenhill, afterwards called Compstall Hall, and Ernocroft Hall, one each for his two sons, George and Charles. They in turn married, Charles to live at Greenhill, George at Ernocroft Hall. They each had six daughters, never a son to carry on the name.

One of George’s daughters married a Mr. Montague Woodmass, a wealthy man who eventually purchased the whole village including the mill and printworks, still going under the named of George Andrew & Son until purchased later by the CPA. Mr. and Mrs Woodmass became the squire and squiress of the village. They, ironically, had five sons and two daughters. Mrs W. was a regular little martinette who demanded obeisance from every child she saw in the village, a bow from the boys a bobbing curtsey from the girls. Should any child fail in this respect the parents’ names were inquired into. The father, who invariably worked at the mill or printworks, was immediately brought to book and severely reprimanded and even in some cases suspended from work for a time. Mrs Woodmass used to punish her own sons, teenagers, for any wrong doing by compelling them to walk through the village in their *Eton suits, with their hands tied behind their backs or with conspicuously light patches stitched to the seats of their dark trousers. The Woodmass’s lost four of their sons in comparatively early years, two on active service, one lost at sea and the fourth in a mental home. George reached middle age.

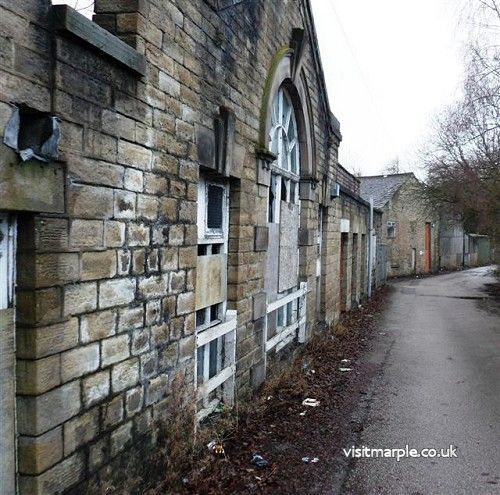

The former print works site at Compstall put up for sale in December 2014. By Bill Beard.The mill and printworks were very prosperous in the early days. Compstall was now spoken of as the modern village, never any short time. The working hours at the mill and printworks were from 6.00 am till 8.00, 8.30 for breakfast, a break, 1.00 to 2 o’clock for the midday meal, then finish at 5.30 pm. Saturday mornings 6.00 am to 12.30pm, a sixty hour week in all. Three and a half days annual holiday from Friday night to Thursday morning. If you were lucky enough to get to the seaside. If you were not lucky enough to get to the seaside there was a general exodus to Belle Vue on Wakes Wednesday afternoon. Other holidays, Good Friday and Saturday, Whit Friday and Saturday.

The former print works site at Compstall put up for sale in December 2014. By Bill Beard.The mill and printworks were very prosperous in the early days. Compstall was now spoken of as the modern village, never any short time. The working hours at the mill and printworks were from 6.00 am till 8.00, 8.30 for breakfast, a break, 1.00 to 2 o’clock for the midday meal, then finish at 5.30 pm. Saturday mornings 6.00 am to 12.30pm, a sixty hour week in all. Three and a half days annual holiday from Friday night to Thursday morning. If you were lucky enough to get to the seaside. If you were not lucky enough to get to the seaside there was a general exodus to Belle Vue on Wakes Wednesday afternoon. Other holidays, Good Friday and Saturday, Whit Friday and Saturday.

One of the highlights of the village was the Scholars Walk at St. Paul’s Church on Whit Friday, done in grand style headed by the local brass band, and a very handsome banner interspersed all along with smaller banners, flags, union jacks, etc. which the girls tried to dodge always because of their hats. We processed to Greenhill, around the grounds and enjoyed the beautiful display of flowers. Then we paraded round the village, stopping at different points to sing. The afternoon was a field day in the cricket field where we had games, sports and were regaled with buns and milk. Generally we got beautiful sunny days for this but if it should be wet we adjourned to the Sunday School.

May 1887 was the Jubilee of St Paul’s Church which coincided with Queen Victoria’s Jubilee, a gloriously sunny day, I remember. How gay the village was with bunting, flags and floral arches all over the place. We did have real summer days then. Most of the school children were half-timers, mill or printworks morning, school afternoon or vice versa, alternate weeks. Those scholars, who were at the mill in the mornings, up before six o-clock, were sometimes too sleepy for lessons in the afternoon. One of the treats for school children was a walk in procession down to the Keg, the shooting lodge of the Andrews where all sorts of sports were provided. One of great fascination was the climbing of the greasy pole with a prize at the top for the lucky climber.

The Athenaeum was a great asset with its weekly penny readings, local talent mostly, which we enjoyed for a penny a time. The Athenaeum has since been used as a day school. Other local treats were the annual Sunday school parties. Every Sunday School had its own party. Each Sunday School teacher had a tray and was the proud possessor of a china tea set which was brought out on this occasion. If she had her own tea urn, better still. With their starched long aprons with embroidered bibs they certainly ruled their allotment of twelve children each. There were piles of ham and beef sandwiches lashed with butter, butter softened on the great iron stove in the middle of the schoolroom. Old fashioned currant bread in plenty, seed and other cakes of all kinds, what a treat!

The Athenaeum was a great asset with its weekly penny readings, local talent mostly, which we enjoyed for a penny a time. The Athenaeum has since been used as a day school. Other local treats were the annual Sunday school parties. Every Sunday School had its own party. Each Sunday School teacher had a tray and was the proud possessor of a china tea set which was brought out on this occasion. If she had her own tea urn, better still. With their starched long aprons with embroidered bibs they certainly ruled their allotment of twelve children each. There were piles of ham and beef sandwiches lashed with butter, butter softened on the great iron stove in the middle of the schoolroom. Old fashioned currant bread in plenty, seed and other cakes of all kinds, what a treat!

About 1883 Glossop Road was known as the new road. At its junction with Compstall Road, then known as Rose Brow, was the toll bar, where once there was a toll gate. The old road from Glossop was via Lane Ends, Cote Green Road down to the Windsor Castle, which continued to Marple Bridge, known as Lower Fold. Rose Brow continued from this point, Windsor Castle, in the other direction to Compstall Bridge. There was a disused coalmine shaft, well protected, in Coal Pit Lane, opposite the Northumberland Arms. The field around was used as a fairground at the annual Wakes time, which fair was previously held on the spare ground in front of the George Hotel near Compstall Bridge.

In 1892 the Bottoms Mill was burned down, during the night, Saturday night, and, as I understand, local residents knew nothing about it until next morning. Sunday, we trudged down through the deep snow to see the blackened skeleton of the remains – a very cold day! We came home to great piles of buttered toast which we truly appreciated.

In 1892 the Bottoms Mill was burned down, during the night, Saturday night, and, as I understand, local residents knew nothing about it until next morning. Sunday, we trudged down through the deep snow to see the blackened skeleton of the remains – a very cold day! We came home to great piles of buttered toast which we truly appreciated.

One of the great events of the village was brass band contest. There were entrants from far and near, each band marching and playing through the village to the cricket field where the contest took place, unfortunately generally pouring with rain. In fact any wet weather afterwards was always spoken of as band contest weather. What a shame it was. The local sports were great events too. Some very valuable prizes were awarded, chiefly given by the Woodmass’s.

One of the favourite walks, especially Sunday afternoons, was by the riverside through the wood which brought us out under the aqueduct and viaduct or through the fields to Romiley. A favourite pastime for the boys was vying with each other in jumping across the aqueduct. One venturesome lad did it with his younger brother on his shoulder. The river path is now impassable the river banks have completely disintegrated.

In the severe winters of those days the mill lodges were completely frozen over to a depth of one foot or more. Only then was skating allowed. It was great fun but very cold. The ice afterwards was broken up and stored in the icehouse in Rollins Lane, free ice for anyone needing it.

One of the gay spots of the village was the grounds of the Spring Gardens Hotel,(below) especially at passtimes. There would be troupes of performers of all kinds, dancers, conjurors, variety entertainers tight rope walking across the deep valley, even Blondin I remember. There was quite a respectable small zoo, gay peacocks strutting around, refreshments and ice cream, etc. Loads of people came from far and near. From here also midnight trips were organised to the seaside, coming back the next midnight, a few sleepy heads before getting home.

The mill workers took their breakfasts with them at 6 o’clock in tin cans and boxes, for breakfast at 8.30, often keeping their cans hot by putting them on the steam pipes. Sometimes the mothers sent down the meal just in time for breakfast. I for one, a six year old, undertook this for a neighbour who lived near the toll bar. To my great consternation the box lid flew open. All the contents scattered on the not-too-clean pavement, bacon sandwiches all about the place. I quickly gathered them, put them together again and never said a word about it. I was quickly out of the mill before anything was discovered but wondered for many a long time what the reactions were – silence – came home and was quickly off to school, St Martin’s, near the station, for 9 o’clock. Quite a day for a six year old.

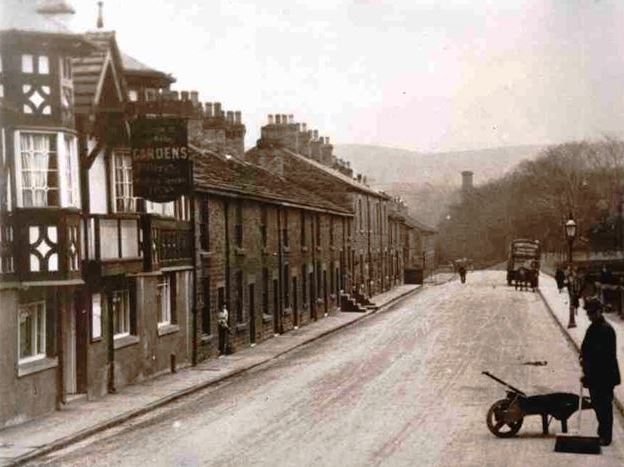

George StreetEach night a blunderbuss, or big gun as it was called, was sounded at 10 o’clock by order of the authorities. What a rush for straying couples to be home by then or soon afterwards, but quite late enough for people to be out who had to be at work so early. There were very few street lights in those days. By 5.30 am you could begin to hear the clatter of clogs on the pavement. Everybody wore clogs at the mill which increased in tempo as 6 o’clock drew near when there was a mad rush to get to the big mill gates before they were closed at 6 prompt. Then the unlucky ones had to wait to be admitted, their names taken, when a fine was imposed and taken from their pay at the weekend.

George StreetEach night a blunderbuss, or big gun as it was called, was sounded at 10 o’clock by order of the authorities. What a rush for straying couples to be home by then or soon afterwards, but quite late enough for people to be out who had to be at work so early. There were very few street lights in those days. By 5.30 am you could begin to hear the clatter of clogs on the pavement. Everybody wore clogs at the mill which increased in tempo as 6 o’clock drew near when there was a mad rush to get to the big mill gates before they were closed at 6 prompt. Then the unlucky ones had to wait to be admitted, their names taken, when a fine was imposed and taken from their pay at the weekend.

House rents were not the great problem in those days. It was an unwritten law that every worker should live in a house belonging to the firm if at all possible. Rents varied from two shillings or less to five shillings for a three bed-roomed house. In most cases, as mill workers, the rent was stopped out of their wages at the weekend.

After a big shoot at the Keg the Powers that be were very generous with their spoils, rabbits galore and for a more favoured few, pheasants. A brace of pheasants was indeed a luxury in those days. Another local walk to be enjoyed on Sunday afternoon was from Compstall Brow just above the church , over the brook into Beacom, on to up-steps and down-steps, through Bottoms Hall Wood, out onto the Glossop Road near the Rock Tavern or alternatively through Beacom onto Werneth Low.

At one stage all the streets and rows of houses were renamed after the Andrews and Woodmass family. In the yard outside the Athenaeum was the band pavilion and two tall chimneys, one belonging to the mill and the other to the printworks. When used as a school playground these buildings provided great cover for games such as hide-and-seek and ball games. The school master in those days was provided with a strap about 7 or 8 inches long, leather, and 2 inches wide, which he didn’t forget to use. I cannot remember how very many times this strap mysteriously disappeared but the mill always obligingly provided another one. The school hours were 9 o’clock till noon, afternoon 2 o’clock to 4 .30, officially, but many times we were kept until 5.30 pm to solve a knotty problem in arithmetic or master a tough phrase in grammar.

Bill Beard, Ruth Hargreaves and Louise Thistleton

Census 1911 of Mrs. Fanny Swindells