When we wrote an article about the Albert Schools a few months ago, one of the illustrations was of a group of a dozen people posing for a photograph. We knew nothing about the people or the date though we could make informed guesses about both. Judging from the clothes the group are wearing it was probably taken in the mid 1920s, assuming of course that Marple folk were keeping up with the fashions. As to who they were, we thought they could be either teachers or governors. The latter was much more likely as they were older, more self-satisfied and more predominantly male than a typical group of teachers. We were fairly sure it was a photo of the governors.

However, we did not know any names so we appealed to our readers and struck lucky. Richard Ebdon recognised the gentleman seated on the left as his 3x great uncle, Frederick Pennington, who was the headmaster of Albert Schools from 1901 to 1931. As the headmaster was sitting on one side of the group rather than in the centre of the row, it was obvious that this group held authority. They were not teachers; they were governors.

Staff or governors at Albert Schools: the gentleman on the front row far left is teacher Frederick Pennington (identified by his 3x great-nephew Richard Ebdon)

Putting together what we knew, with the family history supplied by Mr Ebdon, has enabled us to build a fascinating life story of a middle class Victorian, showing life’s vicissitudes in the days before the Welfare State. Both his parents were from Stockport and his father Samuel was a glass and china dealer but the family moved to Whitehaven in Cumberland to set up in business there shortly before Frederick was born in 1875. Although they were in Whitehaven for a few years it would appear that the business was not a success as his father was declared bankrupt in 1878. By the time of the 1881 census the family had moved back from Whitehaven to live in Salford and two years later his mother Maria entered Nottingham Union Workhouse with her four children in August 1883.

Nottingham Workhouse

Why Nottingham and what had happened to his father Samuel we do not know though we can make an informed guess. Workhouses at this time, although still a very grim option, were not quite as Dickensian as they had been earlier in the Victorian Age but they were still a last resort. Samuel would not have been allowed entry if he had the slightest prospect of making a living, whereas Maria might have been admitted because she was ill - she died a year later back in Stockport. However, there are opportunities in even the grimmest of circumstances and it proved a turning point in Frederick’s life. Within a month of being admitted at the age of eight he was transferred to a dedicated training institution located some distance away in the old Radford Workhouse. This could house 210 children and give them a basic education. At the age of 14 boys were placed out in suitable employment with tradesmen and other employers whilst girls were trained in domestic work. Frederick must have impressed the overseers because the next time we trace him he had gone to the Chester Diocesan Training College to train to be a teacher. By 1891 he was a pupil teacher living in Heaton Norris. His first job as a qualified assistant master was in 1896 at St Matthew’s School in Edgeley but after a year he moved to Marple Albert Schools.

Again, he must have impressed the governors as to his ability because when John Robins, the headmaster, died at the age of 40, Frederick was selected as his replacement at the very young age of 27. He was to spend the rest of his professional life here.

Teacher Frederick Pennington (identified by his 3x great-nephew Richard Ebdon) and class at Albert Schools in 1913.

In 1905 he married one of the teachers at the school, Clara Prentice, two months younger than him, and almost exactly a year later their daughter Margaret was born. As a bachelor Frederick had lodgings in the Heatons and commuted to Marple each day. Now, as a married man and a person of some stature in the community, by 1911 he was living with Clara and his young daughter in Bowden Lane, a seven-roomed house called Norbury Field. It is still there today, one of the first pair of semis near Stockport Road. Sadly, this picture of family life was not to last long. In June 1915 Clara died and Frederick was left a widower to bring up his nine year old daughter alone.

Three years later, in 1918, Frederick married another teacher at Albert Schools, Gladys Prentice, Clara’s 26-year old younger sister. Their father, William Prentice, was a plumber from Great Ancoats in Manchester but he had moved his family to Marple in the 1880s when Clara was about five. They lived at first in Canal Buildings but by 1901 he was obviously prospering as they had moved to Market Street and he is described as an employer. Just as well, perhaps, because there were now eight children in the family ranging from Sarah, a dressmaker age 30 to Herbert age 10. Clara was the next to eldest whilst Gladys was the next to youngest.

The marriage to Gladys was notable because only a decade earlier, it would have been illegal. The Deceased Wife’s Sister’s Marriage Act was passed in 1907 and the title was self-explanatory. During most of Victorian England it was illegal for a man to marry his sister-in-law. Supporters of the prohibition quoted the Bible to make their case but it was easily avoided. Those with money merely went abroad to get married as most other European countries had lifted the prohibition long before. Even so,  it took another thirteen years before women were allowed to marry their dead husband’s brother.

it took another thirteen years before women were allowed to marry their dead husband’s brother.

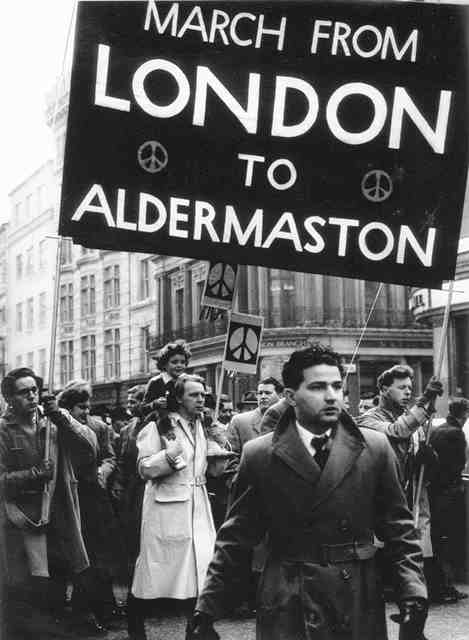

Their only son, Donald, was born a year later and he went on to lead a distinguished career as an academic historian, both at Manchester and Oxford. His special area of study was England in the seventeenth century so it is tempting to speculate that this interest was initiated by the local connection with John Bradshaw. Outside academia he became a founding member of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) and was involved with that organisation from the outset. Donald served as the north-west regional secretary, and a member of the national executive.

Frederick too was becoming recognised in his own field. When the Willows School was opened in 1931 Frederick was appointed headmaster there and he was secretary of the Cheshire County Teachers’ Association. In that role he appeared on a BBC radio programme in 1937, shortly before he retired. The subject of the discussion was “Is there any alternative to school examinations?”, a topic that is still being debated 83 years later. By 1939 he retired from teaching and was living in Hollins Lane with Gladys, his wife. After the war we believe he retired to the Cotswolds and died there in 1956 at the age of 81. A long life and a successful one for someone who had started his career in Nottingham Workhouse.

The recollections of Mrs. Peggy Gould-Martin, born circa 1921, as told in an interview by Gordon Mills. (Peggy was a common ‘nickname’ for Margaret)

I think possibly I ought to tell you a bit about Albert Schools now. I went to Albert Schools until I was 9. It was a dreary kind of a place with a very very small yard and very outdated loos, the ones that tippled. I think they were called “Tipplers”. We had in the infants class Miss Clayton. They gave out like the middle part of a boot where it laced up and we had to learn how to lace our boots up. That was one of the first things we did. I could never master this and I cried bitterly about this. I found it altogether out of my scope. Then from there we moved into Miss Dobson's class. She was strict and she was always threatening to bring the police. If we put our foot wrong. She would say “now I will have the police in”. Well I suppose it did keep us quiet but we were terrified of the police in those days. Then Mrs Meares (?) took the next class and she was the music teacher. She must have been at a funny time of life because her neck used to go very red like a turkey's and she was always fanning herself, so that was Mrs Meares. Then Mrs Swindells. Now Mrs Swindells was a sadist, she had a ruler and if you put your foot wrong she would wrap your knuckles really hard. Then Mr Edwards, he was kind of, would you call him an under-head Master. He had an artificial leg, so we called him “Corky”. Then Mr Pennington who we nicknamed “Boco”. He was tall and thin, a mean looking man and we made a rhyme up about him. We used to sing “Pancake Tuesday is a happy day and if you don't give us a holiday then we 'll all run away. Where will we run to, down Church Lane, see old Boco with his big fat cane”. We used to sing that on Pancake Tuesday. He was terribly strict but I thought we were well taught even so. We did get a good basic teaching but from there you see I went up to All Saints.