St Kilda from the air

St Kilda from the air

‘It is a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma; but perhaps there is a key'.1 Could this describe the thoughts of the hundred plus audience that packed the Independent Evangelical Church on a January evening, on the isle of St. Kilda? Would Don provide the key in his talk? The lights dimmed. “Face the front!”, they did. The chatter faded, a hush enveloped the audience. Let the show begin; let the mystery unravel.

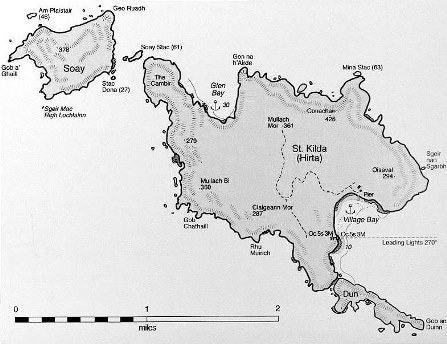

Don took us on a tour of the Archipelago of St Kilda, leading the audience through the geography, history, archaeology, and natural history of the island and the experience of living and working in this remotest of spots, the remotest part of the British Isles, which lies 41 miles (66 kilometres) west of Benbecula , Outer Hebrides.

St Kilda is one of only 24 global locations to be awarded 'mixed' World Heritage Status for its natural and cultural significance. The largest island of group is Hirta, 2.1 miles from east to west , 3.3 miles north to south, the other three islands are Dun, Soay and Boreray. The islands are the remnants of a long-extinct ring volcano rising from a seabed plateau approximately 40 metres (130 ft.) below sea level. Conachair (the Beacon) is the highest point in the archipelago at 430ft. Village Bay is the only modern settlement on St Kilda.

St Kilda was bequeathed to The National Trust for Scotland by the 5th Marquess of Bute in 1957. In the same year, it was designated a National Nature Reserve by the Nature Conservancy. Just before his death, the Marquess of Bute agreed to lease a small area of land on Hirta to the Ministry of Defence as a radar tracking station for its missile range on Benbecula in the Outer Hebrides.

A cleit on St Kilda (overlooking Village Bay)

A cleit on St Kilda (overlooking Village Bay)

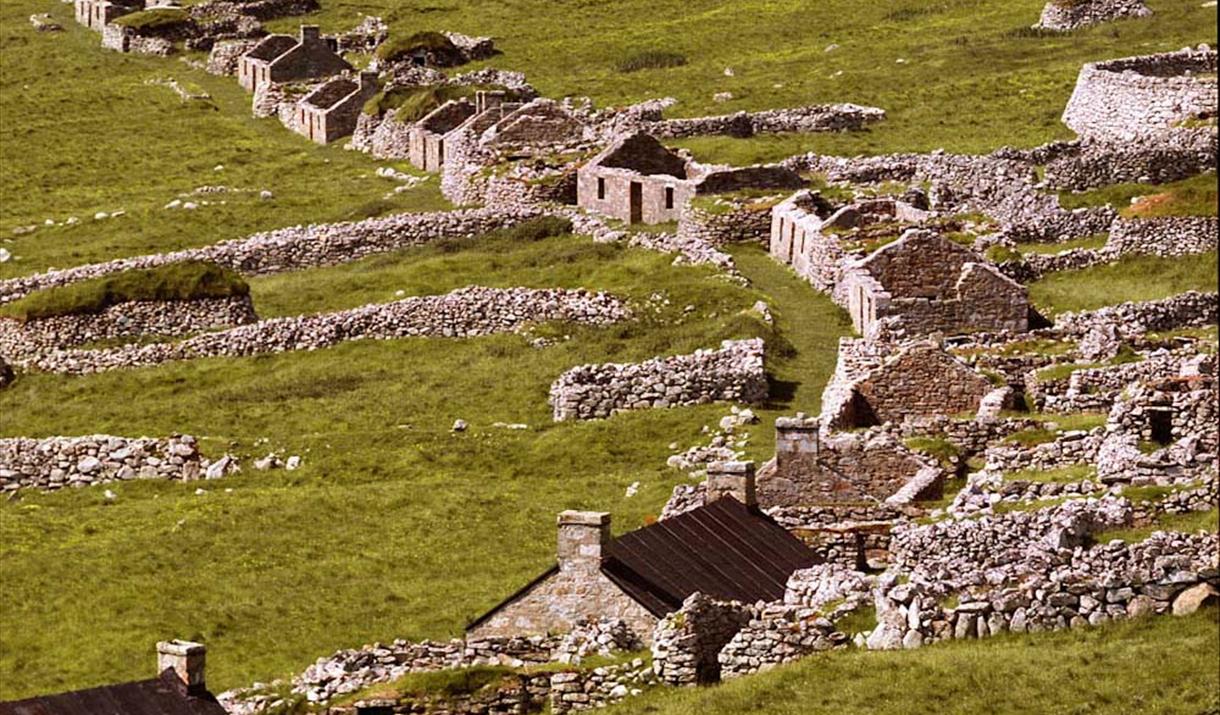

Archaeological and historical research has confirmed that the island has been inhabited, continuously for two millennia, back from the 21st century to the Bronze Age. Recently, the first direct evidence of earlier Neolithic settlement emerged—shards of pottery of the Hebridean ware style,(right) found to the east of the village. The subsequent discovery of a quarry for stone tools on Mullach Sgar above Village Bay led to finds of numerous stone hoe-blades, grinders and Skaill knives in the Village Bay cleitean—unique stone storage buildings.(left)

the Bronze Age. Recently, the first direct evidence of earlier Neolithic settlement emerged—shards of pottery of the Hebridean ware style,(right) found to the east of the village. The subsequent discovery of a quarry for stone tools on Mullach Sgar above Village Bay led to finds of numerous stone hoe-blades, grinders and Skaill knives in the Village Bay cleitean—unique stone storage buildings.(left)

The first written record dates from the writings of an Icelandic cleric wrote, in 1202, of taking shelter on "the islands that are called Hirtir". The first English language reference is from the late 14th. century. Rev. John McDonald arrived in 1822. Previously in 1764, the prescence of five druidic altars was reported by Macaulay, this may have indicated part of the Islander’s philosophy prior to 1822. The island was repopulated in 1727. In 1726 a St Kildan visited Harris, caught smallpox there, and died from it. His clothes were returned to St Kilda in 1727, and brought the disease with them. Most of the islanders died – only one adult and 18 children survived the outbreak on Hirta. However, three men and eight boys escaped the disease as they had been left on Stac an Armin to collect gannets. The disease spread while they were there and nobody could go to fetch them. They were eventually rescued by the Steward nine months later. The owner of St Kilda had to send people from Harris to repopulate St Kilda.

Village Bay, St Kilda, Outer Hebrides

Village Bay, St Kilda, Outer Hebrides

The populat ion survived by harvesting the seabird colonies, cultivating the land, and trading with visitors.

ion survived by harvesting the seabird colonies, cultivating the land, and trading with visitors.

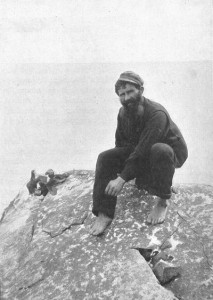

The men were accomplished climbers, and scaled the cliffs to gather the nesting seabirds, and collect eggs from their nests. This included all the islands in the group, meaning a short, but potentially hazardous boat trip in the Atlantic Ocean, where the main danger came from getting on and off the sheer cliffs. This harvest provided them with a source of food, oil, feathers, and eggs, which could be used as payment in kind for their rent. Fulmar oil, which the birds would vomit over any who disturbed their nests, was prized for its supposed medicinal properties.

No trees grow on the islands, and there was little agriculture. Each islander had a plot of land which contained their house, and an area where they could grow their own crops, which included oats and barley. An area to the east of The Village was also cultivated, but has since reverted to natural pasture.

The emigration of 36 islanders to Australia, in 1851, was a blow to island life from which it never fully recovered.

A signal station was established on the island early in World War 1, by the Royal Navy, along with 4 inch gun, after an attack by a German submarine. Daily communications were present for the first time to the mainland.

St. Kilda Evacuation

St. Kilda Evacuation

After World War I most of the young men left the island, and the population fell from 73 in 1920 to 37 in 1928. On 29th August 1936, the remaining 36 inhabitants were evacuated to the Scottish mainland, Morvern, at their own request.

St Kilda is a breeding ground for many important seabird species. One of the world's largest colony of Northern Gannets, totalling 30,000 pairs, amount to 24 percent of the global populatio Soay sheep, from the island of Soay, are a unique survival of primitive breeds dating back to the Bronze Age.

Questions followed, they may have gone on and on. But time was the ruler of the evening. Refreshments were taken, thirsts quenched, curiosity satisfied. Don had produced a key, the audience had unwrapped part of the mystery, the island remains an enigma.

Further Resources

St. Kilda: The National Trust of Scotland

Leaving St. Kilda: Scottish Education, Includes n audio recollection from a former inhabitant of St Kilda, describing the momentous day when he left and his journey to the mainland.

St Kilda - Britain's Loneliest Isle: Scotland on film (several video clips from 1920s onwards)

Abandoned Communities: Since the Middle Ages thousands of towns, villages, and other human communities in Great Britain have been abandoned.

Martin Cruickshank February 2014