The Building of the Manchester Ship Canal by Benjamin Williams Leader

The Building of the Manchester Ship Canal by Benjamin Williams Leader

Judith Atkinson began the talk with a health warning - disciples of Health and Safety might find some of the scenes disturbing. In the event no one chose to leave the auditorium and it was just as well because they would have missed a fascinating description of an engineering marvel. When it was opened on 1st January 1894 it was the largest river navigation in the world and even today it is still the eighth longest ship canal in the world. There are plenty of superlatives to attach to the project including the cost overrun from £6.5 million to £14.5 million but Judith concentrated on describing the actual building of the canal with the benefit of an engineer’s eye.

Using a unique resource of 4000 contemporary glass slides, rescued from a garden shed, Judith took us through the methods and the machinery used and some of the problems encountered. As an indication as to how different things were in the 1890s a bag of cement these days weighs 15 kgs. A generation ago it weighed 56 lbs (25 kgs) and in Victorian times it weighed two hundredweight (101 kgs) To prove the point we were shown a picture of a typical navvy with a wheelbarrow that looked heavier than him. His job was to wheel it up 30 degree slopes filled with earth, all day and every day. (And when he had tipped his load at the top he had to run down in order to keep ahead of the next man.) The job may have been hard but it was well paid. At a time when agricultural labourers were earning perhaps 18 shillings per week these men were paid 5 shillings per day.

of 4000 contemporary glass slides, rescued from a garden shed, Judith took us through the methods and the machinery used and some of the problems encountered. As an indication as to how different things were in the 1890s a bag of cement these days weighs 15 kgs. A generation ago it weighed 56 lbs (25 kgs) and in Victorian times it weighed two hundredweight (101 kgs) To prove the point we were shown a picture of a typical navvy with a wheelbarrow that looked heavier than him. His job was to wheel it up 30 degree slopes filled with earth, all day and every day. (And when he had tipped his load at the top he had to run down in order to keep ahead of the next man.) The job may have been hard but it was well paid. At a time when agricultural labourers were earning perhaps 18 shillings per week these men were paid 5 shillings per day.

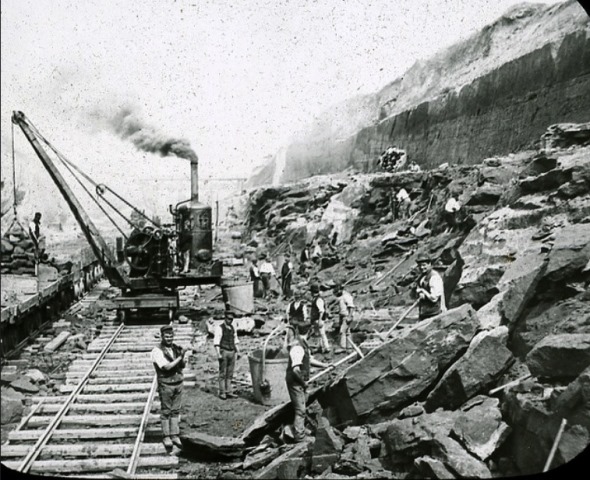

There may have been 16000 navvies but most of the excavation was carried out by machine and Judith proceeded to show us some of the steam-powered equipment. 120 steam cranes, 97 steam excavators, 180 locomotives running on 200 miles of track. All very impressive but some of the scaffolding and other working practices were rather less impressive. Planks supported by cross planks, gunpowder lying around on site, fifty foot ladders that had rungs nailed in place, “kamikaze” scaffolding that was at least 90 feet high and due to rise another 90 feet. Good practice with machinery was no better; cranes lifting three times their rated loads, overladen tipping trucks and locomotives that regularly tipped over only to be put back in place by half a dozen navvies with crow bars.

Judith took us through  Group of workers with steam navvy during constructionall of these practices and it was no wonder that in the six years of building there were 6500 serious accidents and 120 men killed. This sounds horrendous but, for its time, this project had a good reputation for safety and for looking after its workforce. There were nine accident hospitals along the 36 miles of the canal and every site train had an accident car attached to it. These hospitals anticipated the triage system which was developed during the First World War and every man who was injured was guaranteed a job when he recovered from his accident.Yes, the job may have overrun its cost budget and its completion time but so do projects in the twenty-first century. This was engineering on the grand scale and for all its problems, it completed half a mile of canal every month. No modern motorway builder could claim that.

Group of workers with steam navvy during constructionall of these practices and it was no wonder that in the six years of building there were 6500 serious accidents and 120 men killed. This sounds horrendous but, for its time, this project had a good reputation for safety and for looking after its workforce. There were nine accident hospitals along the 36 miles of the canal and every site train had an accident car attached to it. These hospitals anticipated the triage system which was developed during the First World War and every man who was injured was guaranteed a job when he recovered from his accident.Yes, the job may have overrun its cost budget and its completion time but so do projects in the twenty-first century. This was engineering on the grand scale and for all its problems, it completed half a mile of canal every month. No modern motorway builder could claim that.

An excellent talk presented with the right mix of expertise and humour and illustrated with magnificent photographs.

Thank you, Judith.

Neil Mullineux - March 2015

Manchester Archives+ flickr page of images on the building of the Ship Canal