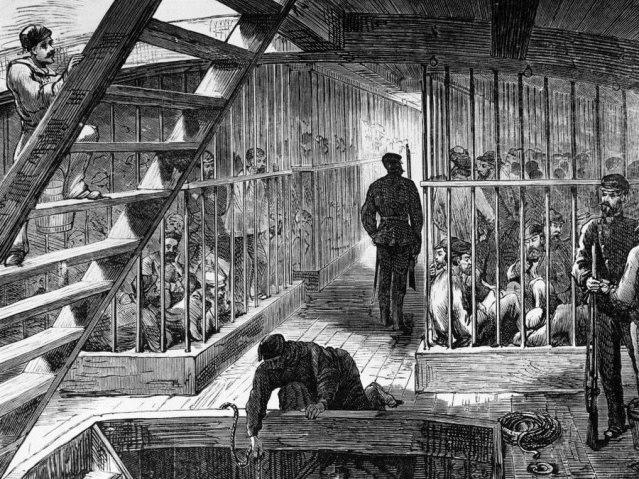

Conditions on a convict ship to Australia

Conditions on a convict ship to Australia

The website promised us a gripping tale and that is exactly what we got - a steady rise to a position of some eminence in local society - a dramatic fall from grace - a slow climb back then, once again, disgrace and punishment. A very Victorian moral tale worthy of Charles Dickens. And it all happened to a local man. Neil first discovered this fascinating episode when reading Tony Jones’ book on Bridges, Highways and Turnpikes and then found out much more as he researched the Isherwood family at Marple Hall.

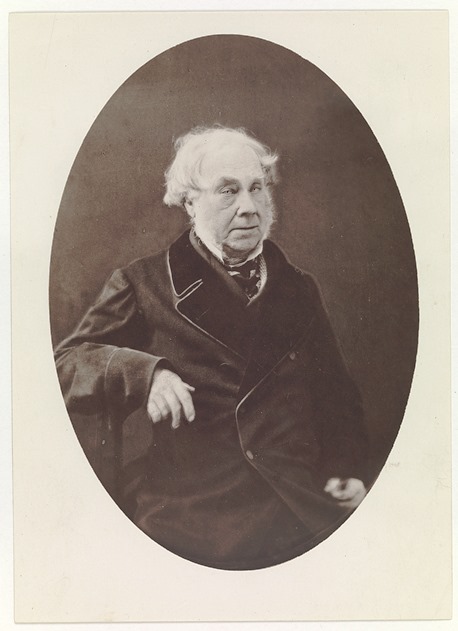

John Kenyon WinterbottomJohn Kenyon Winterbottom was a local Stockport solicitor who had earned the trust of most of the eminent families in this part of Cheshire. He had worked his way up from articled clerk to his own practice, founding Stockport’s first bank and taking on the role of mayor by the time he was 40. Unfortunately he over-reached himself and made several unwise investments. In order to avoid bankruptcy he began to use his client’s money. It was to no avail. He was declared bankrupt anyway but his dishonest actions were also exposed, including the theft of a £5000 life insurance policy from the Isherwood family.

John Kenyon WinterbottomJohn Kenyon Winterbottom was a local Stockport solicitor who had earned the trust of most of the eminent families in this part of Cheshire. He had worked his way up from articled clerk to his own practice, founding Stockport’s first bank and taking on the role of mayor by the time he was 40. Unfortunately he over-reached himself and made several unwise investments. In order to avoid bankruptcy he began to use his client’s money. It was to no avail. He was declared bankrupt anyway but his dishonest actions were also exposed, including the theft of a £5000 life insurance policy from the Isherwood family.

Days before this all came out into the open he fled to escape justice and was on the run for four years. Eventually he was recognised and taken prisoner in Liverpool in 1844. By this time he was a cause célèbre and his trial attracted many column inches of space in newspapers throughout the country and overseas. Forgery was a serious charge. A generation earlier it would have attracted the death penalty but instead he was sentenced to transportation for life.

Neil’s talk followed his progress from Chester Jail to Millbank Prison and then on the convict ship, taking five months from Woolwich to Australia. The final destination was Norfolk Island - a name associated with a savage regime and bestial conditions. At the age of 58 it must have come as a real shock to Winterbottom after a comfortable middle-class life in Stockport. Conditions were such that there was a full-scale mutiny within six months. It was put down and all the ringleaders were hung but it was a rude awakening to prison life for John Winterbottom.

Millbank Prison

Millbank Prison

He was given some small responsibilities as a prisoner and he kept a clean record, both in Norfolk Island and when he moved to Tasmania. A model prisoner, he had jobs with a variety of private companies and seemed to be an exemplary employee. But only up to a point. On one occasion, he and a companion got drunk, stole a hat and were given a month in prison despite the pleas from his employer.

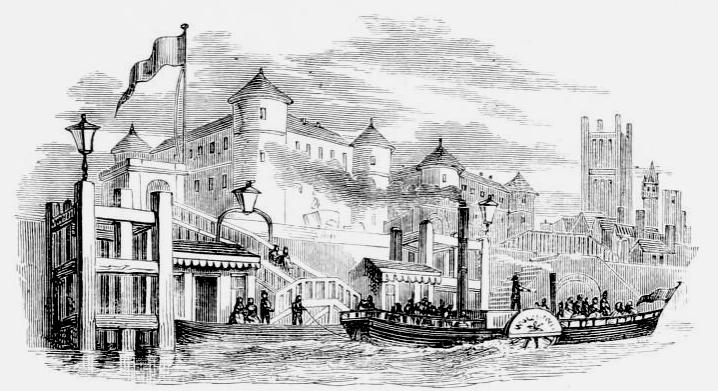

Eventually he received his ticket of leave and he was a free man but with certain conditions. It was an exciting time to be in Tasmania. It was becoming established as a separate colony and was no longer Van Diemen’s Land as it had been known till then.  Hobart Town HallThey needed a town clerk and Winterbottom applied. There were 14 other applicants but who better than an ex-town clerk of Stockport? His rehabilitation seemed complete. At the age of 71 he had an important and very responsible job, controlling the administration of the new and rapidly growing town and taking overall charge of the building programme for the new town hall and spent his last few years as a free man, dying in Hobart in 1872. An eventful, if not blameless life.

Hobart Town HallThey needed a town clerk and Winterbottom applied. There were 14 other applicants but who better than an ex-town clerk of Stockport? His rehabilitation seemed complete. At the age of 71 he had an important and very responsible job, controlling the administration of the new and rapidly growing town and taking overall charge of the building programme for the new town hall and spent his last few years as a free man, dying in Hobart in 1872. An eventful, if not blameless life.

He saw this through successfully and was the first town clerk to have an office in the new building but then disaster struck once more. He had been embezzling council funds and was accused of fraud. Once again he was found guilty and this time was sentenced to two years imprisonment. He survived this and spent his last few years as a free man, dying in Hobart in 1872. An eventful, if not blameless life.

Neil finished his talk by reviewing Winterbottom’s legacy. Unfortunately many of our modern politicians have not learned from his example and there was a roll call of perjurers, thieves and fraudsters from the recent past. The only difference seems to be that the modern politicians had far more lenient sentences.