Joanna Williams

Manchester is famed for its support of radical political movements - the Co-operative movement, the Anti-Corn Law League and the Trades Union Congress. But perhaps the movement most closely associated with this city is the fight for women’s suffrage. In 2021 we heard from Andrew Simcock about Emmeline Pankhurst but at our October meeting Joanna Williams introduced us to a lesser known figure who played a very important role in the growth of the suffrage movement - Lydia Becker.

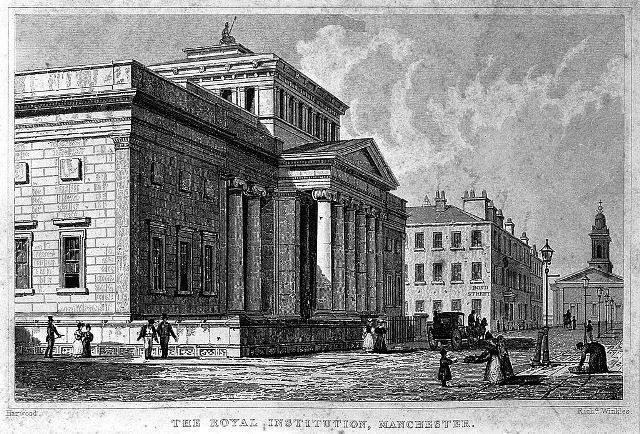

The Manchester Royal Institution (Manchester Art Gallery)

Lydia Becker was the daughter of a well-to-do family originally from Germany. Her grandfather had established a business supplying dyes and chemicals to the cotton industry and her mother was the daughter of a Hollinwood mill owner. Like most girls at the time she was educated at home but she developed an early interest in science, particularly botany. An uncle encouraged this interest but her mother died when Lydia was 28 and she spent a lot of time looking after her eleven siblings. Nevertheless, she was awarded a gold medal for a paper on horticulture and she published a book on botany, “Botany for Novices.” At a more academic level she had ongoing correspondence with a number of prominent scientists.

Moorside House - the Becker's home before the American Civil War

The American Civil War had a devastating effect on the Lancashire cotton industry as the supply of raw cotton dried up and the Becker family firm suffered equally. The family moved to Ardwick and, soon after, Lydia moved into her own lodgings in Greenheys, less than two miles away. It was here that Lydia, freed from many family responsibilities, found her independence. Her practical study of flowers came to an end but she still continued her correspondence with Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace, another naturalist with an international reputation. She took the first steps to becoming a public persona when she was nearly 40 by founding the Manchester Ladies Literary Society. The name was somewhat misleading as she intended it to be a scientific society for women and she was sent three scientific papers by Charles Darwin to be read and discussed at early meetings.

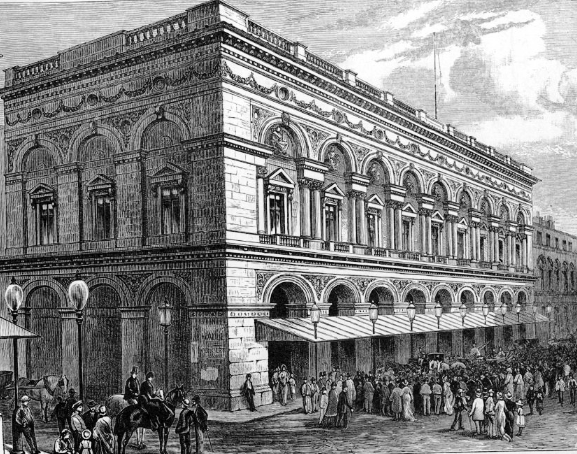

Manchester Free Trade Hall in 1870

Soon after she attended a meeting where Barbara Boudichon, an early feminist and women’s rights activist, gave a paper advocating the enfranchisement of women and it was a Pauline conversion for Lydia. From that moment she became a political activist. The first step was to organise fellow sympathisers and she convened the Manchester Women’s Suffrage Committee, the first of its kind in England. Within two years this morphed into a much bigger organisation - the National Society for Women’s Suffrage and the first meeting was held in the Free Trade Hall. She threw herself into many trail blazing activities and she had a natural flair for publicity which helped. Some of these ventures were successful; others less so. She identified some women whose names had accidentally been placed on the electoral register and in co-operation with Richard Pankhurst (later to marry Emmeline) she brought their claim to court but was unsuccessful. However, in other ways she was instrumental in making the first moves towards enfranchisement by securing votes for women in municipal elections and for representation on school boards.

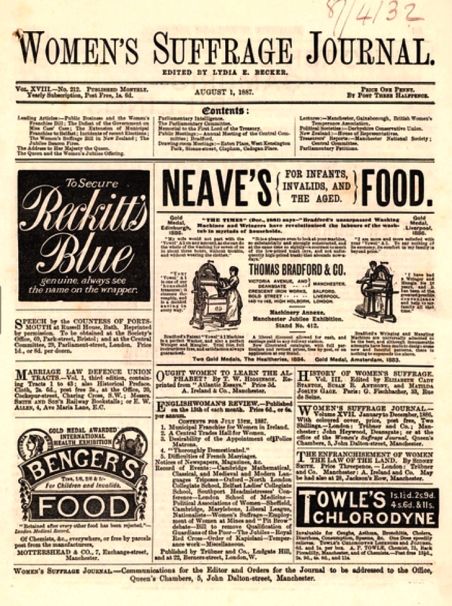

Perhaps the major work of her life was the establishment and publication of the Women’s Suffrage Journal, the most popular publication of its type in Britain. She used it as a vehicle for promoting speaking tours of women which had been a rarity until that time. A notable achievement was the campaign in 1880 to give women the vote in the Isle of Man. This success was unexpected but it was a marker for subsequent enfranchisements in New Zealand and eventually the United Kingdom. She had powerful support in that both Disraeli and Salisbury as well as many MPs were in favour of votes for women. Unfortunately she had equally influential opponents including Gladstone and Queen Victoria.

Lydia Becker was a trailblazer in that she was ahead of most of her contemporaries in the suffrage movement. She was a strong supporter of education for women and believed there was no difference between the intellect of men and women so she advocated non-gendered education. She campaigned for the inclusion of women on school boards and was a member of the Manchester Board of Education for over twenty years. Rather more controversially she supported the rights of single women as more urgent than for married women, a stance that was not widely accepted. What she did not support was violent action but that did not come about until twenty years after her death when Emmeline Pankhurst decided that peaceful protest was not getting anywhere.

Lydia Becker was a trailblazer in that she was ahead of most of her contemporaries in the suffrage movement. She was a strong supporter of education for women and believed there was no difference between the intellect of men and women so she advocated non-gendered education. She campaigned for the inclusion of women on school boards and was a member of the Manchester Board of Education for over twenty years. Rather more controversially she supported the rights of single women as more urgent than for married women, a stance that was not widely accepted. What she did not support was violent action but that did not come about until twenty years after her death when Emmeline Pankhurst decided that peaceful protest was not getting anywhere.

Nevertheless, Joanna made an excellent case that Lydia Becker was at least the equal and possibly more important than Emmeline Pankhurst in the long fight for the emancipation of women. Perhaps we should arrange another meeting and invite Andrew Simcock back again with each arguing for their respective heroines.

Neil Mullineux - October 2024

Further Reading:

- Lydia Becker School for Science a challenge to domesticity by Joan Baker from the Womens History Review

- Lydia Becker at the Darwin Project