I was very gratified today. Nearly forty visitors came to see my mill. They all seemed to know that it was the biggest cotton mill in the world when it was built though some of them were a bit hazy as to how it worked. Richard Arkwright’s father had first come up with the idea of a manufactory or a factory as they call them now. His brilliant idea was to bring the workers to a place of work rather than taking work out to them in their homes. Admittedly, there was the expense of providing the building but you had to do that anyway because these new water frames were far too big to go into workers’ hovels. No, the big advantage of bringing the workers all together was so you could control them more easily. You could control the hours they worked, when they worked and the quality of their work.

Richard and I got to know each other well, when we were youngsters in Nottingham together, and we remained close friends as we were making our way in the world. I had become the biggest manufacturer of muslin in the country by the age of thirty, whilst Richard was running much of his father’s business for him, particularly after he was knighted in 1786. Richard had already lent me £3000 to build a mill in Stockport and I had rewarded him with a very big return on his investment by 1787. At that point we decided to design and build the best and the biggest mill in the world in Mellor. Things had moved on a lot since the first Cromford Mill in 1772 and there were 143 mills using variations of that design. Richard and his father had investments in 110 of them so Richard had a wide experience to go with my practical knowledge.

Richard and I got to know each other well, when we were youngsters in Nottingham together, and we remained close friends as we were making our way in the world. I had become the biggest manufacturer of muslin in the country by the age of thirty, whilst Richard was running much of his father’s business for him, particularly after he was knighted in 1786. Richard had already lent me £3000 to build a mill in Stockport and I had rewarded him with a very big return on his investment by 1787. At that point we decided to design and build the best and the biggest mill in the world in Mellor. Things had moved on a lot since the first Cromford Mill in 1772 and there were 143 mills using variations of that design. Richard and his father had investments in 110 of them so Richard had a wide experience to go with my practical knowledge.

We came up with a long narrow building, six storeys high. By making it only 33 feet wide and 400 feet long, we could get as much light as possible into each floor and we needed that because of the thin cotton thread we were working with. My masterstroke was to have the water wheel in the centre of the building and the water going straight through, from the millpond, through the breast shot wheel then into the Goyt. This gave a very efficient source of power to both wings of the building on all six floors. A mill as big as this would be expensive but it would be very efficient and the demand for muslin seemed inexhaustible at that time. So, we went ahead. I mortgaged myself up to the hilt and Richard came in as well with a substantial loan. It was a big risk but we both knew what we were doing.

Anyway, back to 2013. I was surprised and somewhat shocked to see someone impersonating me as he showed people round the site. I’d heard of the Bootleg Beatles and those ludicrous Elvis impersonators but this seemed a bit too much. He didn’t have my classical good looks and, although he had a fine leg, it certainly didn’t compare with mine. Still, he knew a little bit about the mill and he was very enthusiastic. I can forgive a lot if someone shows ent husiasm. Fortunately none of the visitors had arrived on horseback. We had made provision for this when building the mill but we hadn’t expected more than four or five at a time, certainly not 37. Most of them turned up in rather ugly metal carriages – not a horse between them. Still, they were well-behaved and fairly orderly.

husiasm. Fortunately none of the visitors had arrived on horseback. We had made provision for this when building the mill but we hadn’t expected more than four or five at a time, certainly not 37. Most of them turned up in rather ugly metal carriages – not a horse between them. Still, they were well-behaved and fairly orderly.

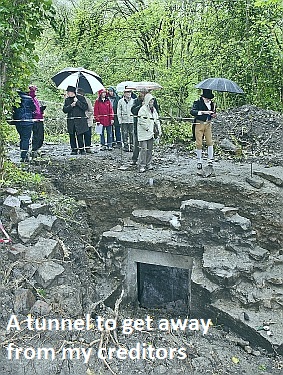

They had a look at the mill foundations then inspected the wheel pit. The archaeologists had certainly made a good job of clearing it out and providing inspection platforms. Then they had a look around the mill buildings - the retort house, the workshops and the stables, before moving on to see the Waterloo wheel pit. That really did impress them. Not so much the clever way we had brought additional power into the mill but the ingenious way we routed the water. The same water was used to power both wheels and then we took it under the river and 600 yards downstream in order to return it. After that the guides showed them my private tunnel from Mellor Lodge to the mill yard. I must admit I did rile at that. It was very intrusive and an invasion of my privacy. I would certainly not have allowed it if I had been showing them round. Still, after two hundred years I suppose I can’t object too much. At least they all made a contribution to the fund for restoring the site. When I was in charge, a week’s wages would be ten shillings but these days that wouldn’t go anywhere. We’ll need a lot more than that if we are going to restore the mill properly so please tell your friends.

![]()

From our eighteenth century correspondent

The photographs are copyright Arthur Procter, whom we would like to thank for his work.

The Official Opening of the Wellington Wheel Pit, in March 2012, can be on YouTube at..

Far more information on Mellor Mill, visit the Mellor Archaeological Trust website ....