The flight of sixteen locks is one of my favourite places in Marple. A walk down to the aqueduct is peaceful but not lonely. You pass the occasional boater struggling with the lock mechanism, panting runners, dog-walkers exercising themselves rather than their dogs and people doing much the same as you are. A quiet and tranquil promenade to start the day or to wind down after a stressful afternoon. But it was not always thus as Steve Gent demonstrated on our July walk. The whole flight of locks was a hive of activity with boats loading and unloading, warehouses, lime kilns, coal yards, support trades and new industries such as boat building, all working together and in competition with each other. It was not industry in the sense of the dark satanic mills of Stockport or Ashton or Oldham but it was industry nevertheless.

Artists at Lock 13 work on their compositions for an art competion

The first canals used coping stones along their banks to protect the puddled clay and provide a firm surface but these coping stones differed in terms of the use they had to face. On the towpath side of the canal the coping stones were substantial and usually had a smooth finish whereas on the off side they were not subject to close scrutiny and they were often rough and unfinished. However, the coping stones used for wharves and other areas of industrial activity were bigger and more substantial than these as they had to withstand much greater loads. A typical wharf would have both a 30 hundredweight and a three ton crane and they were made to work hard. So our clue was to look out for large coping stones as they would indicate the presence of a wharf.

The curtains open on the evening's stroll, by Aqueduct House

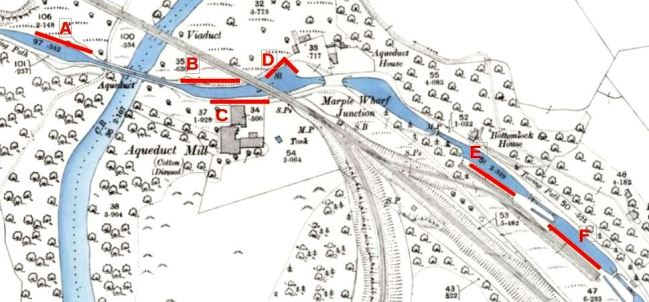

The first wharf was not on the lock flight at all but on the Romiley end of the aqueduct. When the Upper and the Lower canals had been completed the company ran out of money to build the locks so, as a temporary measure, had built a tramway between the two levels. It was here that the tramway ended, at a wharf to load the stone back onto boats for the onward journey into Manchester. It is not known how the trams crossed the Goyt to reach here; did they have their own temporary trestle or a scaffolding extension above the growing stone aqueduct? Either way it must have been a scary experience for the men working on the aqueduct to have a three ton truck, laden with stone, rolling along a very flimsy set of rails immediately above you. Fortunately they did not have to endure this for long; as soon as the aqueduct was complete the terminus was moved to the south end of the aqueduct, giving a shorter, safer run and more room for the boats to turn round. The site of this new wharf was on the off side of the canal, adjacent to where the Engineer’s Wharf is now, though at that early stage it had not been built.

A Terminal wharf for tramway before completion of aqueduct

B Terminal wharf for tramway after completion of aqueduct

C Passenger wharf at Queen’s Hotel. Later the wharf served Aqueduct Mill

D Engineer’s Wharf

E Later wharf constructed for transferring from wagon to boat

F Later wharf constructed for transferring from boat to wagon.

Opposite, on the towpath side, and close to where the Queen’s Hotel would shortly be built, was another wharf. This was used first as a passenger landing stage where passengers on the swift fly boats disembarked to finish their journey to Marple. Once the locks were completed this area became a waiting area for boats, letting them tie up to await their turn to ascend the lock flight or to cross the aqueduct. Then, at a much later stage, when the Aqueduct Mill had been built, it acted as a normal commercial wharf delivering and loading cargoes.

The final wharf before entering the lock flight proper is Engineer’s Wharf, the company wharf used for servicing and maintaining the canal. There is an expanse of level space for the storage of materials (stone, timber etc) and for many years there was a blacksmith’s shop and a carpentry shop though these have now been demolished. These provided a service to the canal users such as horse shoeing and minor boat repairs though anything major such as replacement lock gates was carried on at central, specialised workshops. There were usually similar facilities for minor repairs on every canal as time was money in a very competitive business.

Once we entered the lock flight the first wharves served a unique purpose, working to facilitate the building of the new railway to New Mills and beyond. The viaduct was completed in 1862 and a cutting was made from the main line to the canal with two sets of sidings - one alongside the Lock 1 pound, the other alongside Lock 2 pound. At first sight this seems unnecessary but the layout takes advantage of the differing heights of the locks. The northern siding was above the water level of the canal so cargoes could easily be transferred from railway wagon to narrowboat. The more southerly siding, alongside Lock 2 was below the canal level which helped the transfer of loads in the opposite direction, from boat to wagon. Although only intended as a temporary expedient during the construction of the railway, it proved so useful that it was kept in place and operative for many years. It was only taken up in 1900.

As well as research into wharves, Steve has also been looking into the careers of some of the boatmen. It was a hard life for all and as the railways prospered, the canals suffered. Nevertheless some achieved considerable success from a very low base. James Hall who was born in Bugsworth to a boating family gradually built up a fleet of twenty boats. John Green of Macclesfield did even better. Based in Macclesfield, he specialised in shipping coal and pottery from Stoke and return trips from Manchester carrying mainly cloth. He eventually finished operating eighty boats. You did not necessarily specialise in high value goods. James Pott had a fleet of open wooden boats used for carrying stone, a very low value commodity, but he prospered by specialising all aspects of his business and concentrating on a single product.

Until we reached Lock Nine we had not come across any specific contribution from Samuel Oldknow but there his innovative ideas were on full display. The warehouse he built there is designed to both facilitate and to maximise transfers between land and canal. There were facilities for loading and unloading boats both under cover and in the open. Similarly transfers to and from horse-drawn carts could be carried out in all conditions. By law he had to allow public use of his wharf and he provided cranage and wharf space but he also charged for the use of the private roads that served the wharf. He owned the full length of road from the warehouse to Mellor Mill, another example of his total approach to business.

Just above Oldknow’s warehouse, on the off side of Lock Ten was a small coal yard although there is now a house on the site. Originally owned by Oldknow, it was used mainly for Mellor Mill and ownership passed to Arkwright on the death of Oldknow. However, the most industrial activity is centred around Lock Twelve. Two private branches join the main canal at this point. The earliest is the short branch going to the lime kilns built by Oldknow and linked with the canal from the start. Again, Oldknow demonstrated his advanced thinking as he had with his warehouse. There were two sheds for storing and shipping the finished burnt lime, one for boats and the other for wheeled carts. Both were served by a short tramway from the kilns. The boat shed could load two boats at a time under cover and the other shed gave similar protection for carts. Somewhat later another branch was created leading to Hollins Mill. This was used to bring in raw cotton and coal and to take out finished goods. Both of these branches resulted in more traffic through the canal but the wharf based activity was what made this an important working node. Roughly half the wharf area was owned by the canal company and used as a public coal yard for the district. As a result of this the whole wharf was given the name ‘Black Wharf.’ The remainder of the area was predominantly a timber yard but there was also a blacksmith and some small metal workshops.

The final industrial area was at Top Lock where initially Oldknow had planned both the upper part of his lime kilns project and a boat building yard. The kiln heads were accessed by the Higher Private Branch which opened out into a small basin, Marple Basin. From here there were two short canal arms, little more than tight berths for boats to get as near as possible to the kiln heads. There they unloaded the two main cargoes of coal and limestone. Another short arm from the basin led to a dry dock facility for the boatyard.

The final wharf on the lock flight was the Tramway Wharf which formed the top terminal of the Marple Tramway. It had a very active life for the seven or eight years of the tramway’s existence but when that was dismantled, the summit warehouse which had been built to facilitate the transhipment of goods, was converted into a corn mill, another of Oldknow’s ideas. This used water from the canal as a power source and gave the Tramway wharf a new lease of life. By the 1850s it was proving unprofitable and it underwent another conversion, this time into a mineral mill. This concentrated on making specialty minerals such as plaster of Paris, barytes, Venetian Red and Mineral White but it required regular shipments of materials and goods using Tramway wharf. It passed through several owners, eventually being owned by J & M Tymm but when the lime works closed in 1902 the Mineral Mill had to close too.

This was the death knell for Tramway Wharf but the physical assets remained until purchased by Steve Gent with an eye to developing it as an historic site. Longer than most wharves, it can accommodate at least five full-length boats and Steve ended his walk by explaining his ideas and plans for developing the wharf.

An excellent walk led by an expert and it opened our eyes to just how busy Marple Locks had been in their heyday. And if we weren’t already aware, it brought home to us just how innovative and far-thinking Samuel Oldknow had been.