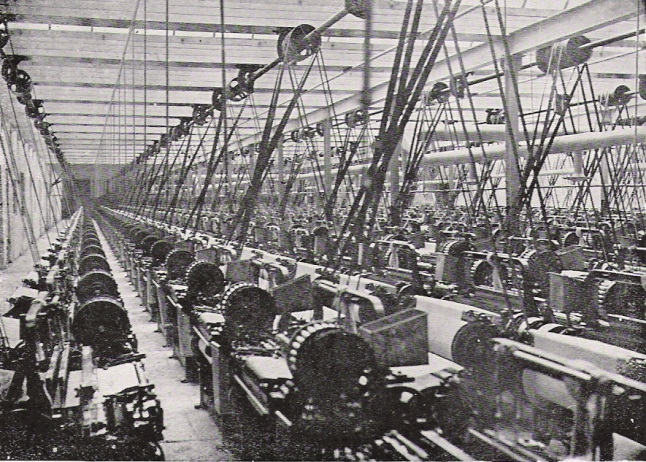

Steam powered weaving shed 1914

In March 2015, Judith Atkinson gave us a fascinating and entertaining insight into the building of the ‘Big Ditch’ - the Manchester Ship Canal, using a remarkable collection of glass slides. This evening, Judith excelled again, using an album of photographs that had narrowly missed being discarded in a skip to illustrate her talk about the working life of the Burgess-Ledward mill at Walkden.

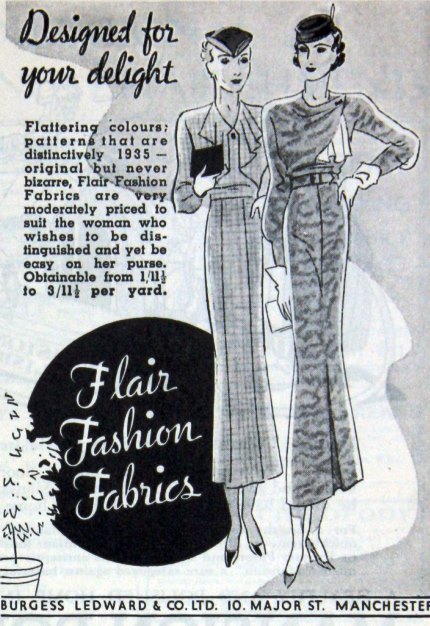

Originally a workshop opene Dyeing Shedd in the 1860s by Mr Burgess, the business became Walkden’s first textile mill. Expansion came when Mr Ledward, a Manchester textile merchant who bought cloth from the Company, became a partner. Initially there were 250 looms, which, by the late 1890s, had grown to 1500. In 1894 Burgess’s son came into the business and a dye house was added, large enough to bleach and dye the yarn spun by other mills in the area. Burgess junior was sent to Germany to learn about dyeing and returned several years later as a qualified chemist. It was at this time that the dyeing business expanded rapidly.

Dyeing Shedd in the 1860s by Mr Burgess, the business became Walkden’s first textile mill. Expansion came when Mr Ledward, a Manchester textile merchant who bought cloth from the Company, became a partner. Initially there were 250 looms, which, by the late 1890s, had grown to 1500. In 1894 Burgess’s son came into the business and a dye house was added, large enough to bleach and dye the yarn spun by other mills in the area. Burgess junior was sent to Germany to learn about dyeing and returned several years later as a qualified chemist. It was at this time that the dyeing business expanded rapidly.

Soon the business was a major employer in the town. However, as Judith explained, Mr Burgess was not just interested in profits. He was a man of liberal principles and promoted education for his employees, encouraging Walkden Council to provide evening classes for workers, which led eventually to a day release scheme. From 1910 Burgess Ledward also provided health care in the form of an ambulance room staffed with nurses. Subsequently, a local mansion was purchased to provide a welfare centre.

Of course, we must remember that all mills were dangerous places to work in. Bleaching and dyeing was a primitive and dangerous enterprise and remained so well into the twentieth century. Judith’s photographs from the 1920s clearly showed this. Workers in the  dyeing and bleaching processes worked with toxic chemicals without protective clothing and spent chemicals were routinely poured into the river and drains! In the weaving shed, which at its height employed over 1400 people, the noise would have been overwhelming. No wonder the workers learned to lip-read.

dyeing and bleaching processes worked with toxic chemicals without protective clothing and spent chemicals were routinely poured into the river and drains! In the weaving shed, which at its height employed over 1400 people, the noise would have been overwhelming. No wonder the workers learned to lip-read.

The photographs allowed Judith to take us on a tour of the premises, showing us the bleaching and dyeing processes, how the raw yarn was prepared for the looms and then the weaving sheds where the cloth was woven. The mill generated its own power, with a boiler room containing 14 Lancashire boilers of which 12 were used for the dye house. The Lancashire boiler was the workhorse of the boiler industry during the first part of the 20th century and could be used for either steam or low-pressure hot water heating systems.

Working in any kind of mill was a hard life. Much of the work was repetitious and the hours were long; conditions difficult and sometimes dangerous. Decline came in the late 1950s, as it did for many mills, including Hollins Mill in Marple. Weaving stopped in 1968 and the mill finally closed in 1985. After a devastating fire, the mill was demolished in 1990 and houses built on the site. Our thanks to Judith for another informative and entertaining talk.

Hilary Atkinson, November 2018