Following his successful talk to the Society about the Peterloo Massacre, Jonathan Schofield conducted a tour of where it all happened. There were 36 of us - a very impressive turnout.

First, he had to set the scene. In 1819 St Peter’s Field was on the edge of Manchester. It was gradually being built up so there were some houses and gardens as well as open space and uncompleted roadways. Moseley Street was an area of wealthy houses and St Peter’s Church stood at the junction of Moseley Street and Oxford Street, where the Cenotaph now stands. There was no Town Hall, no Library and no Midland Hotel.

Manchester was a hotbed of radicalism and the centre of a growing industrial activity centred around textiles and, particularly, hand loom weaving. These men were the aristocrats of the working class - independent, free thinkers and high earners. Or at least they had been high earners but no longer. The end of the Napoleonic Wars, the introduction of the Corn Laws and the gradual spread of mechanisation in the weaving trade had all come together to impoverish these proud workers. They were now earning only a third of what they had been earning a decade before.

The meeting had been well-planned and well-organised. There was plenty of publicity to attract a large crowd and organised groups of several hundred were coming from as far away as Blackburn, a good twenty miles, as well as from Bolton, Wigan, Oldham and Stockport. The intention was emphatically peaceful. They believed that sheer numbers would make an impression on an unfeeling government. At the same time the publicity alerted the authorities. They were anticipating trouble and made appropriate preparations with special constables on duty and both regular troops and volunteer militia standing by.

We began by looking at some original weavers cottages in the area. This was a surprise for even the most hardened historians in our group but if you look at the Grey Horse Inn in Portland Street or The Vine or the City Arms in Kennedy Street there are the trademark loft windows. As a bonus we were informed that the Grey Horse Inn has the smallest bar in the country though we think the Hatters in Church Lane could run it close. It is also in this area that the Yeomen Cavalry (of which more later) gathered in Pickford’s Yard. Pickford is, of course, the carrier from Poynton who by 1819 was nationally significant.

An excellent vantage point to discuss the events of the meeting is on the open ground in front of Grand Central. In 1819 this was St Peter’s Field and the ground sloped gradually down to the Medlock. Nowadays the ground slopes UP towards Grand Central because Central station had to be built on the same level as Liverpool Street station. 38 million bricks were used to bring it up to this level. Unfortunately Don won’t be using this classic piece of trivia in “Curious Cheshire” as Central station isn’t in Cheshire but it’s a useful fact for all historians to absorb.

Turning our backs on the slope to the Medlock, where the Hussars were stationed on that fateful day, we now face the Midland Hotel. Two hundred years ago a walled area of houses and gardens occupied the same footprint and it was in one of these houses that the local magistrates settled to keep an eye on proceedings. They had a clear view down to the Radisson/Free Trade Hall where the speakers gathered on the hustings. This was a rather grand name for two carts lashed together in order to provide a platform for the speakers. Between these two opposing points, no more than 90 metres apart, stood a long line of 400 special constables. There were, perhaps, 60,000 people in the crowd with more arriving all the time. When Henry Hunt was due to address the crowd, the magistrates lost their nerve and sent messages to bring in the Yeomanry and the Hussars. The Yeomanry arrived first and they were ordered to arrest Hunt, a task they accepted with drunken enthusiasm. They plunged into the crowd, wielding their sabres to clear a path but getting hopelessly entangled in the mass of people. At this point the Hussars arrived from the area near today’s Bridgewater Hall and they were ordered to rescue the amateurish Militia from the crowd. They were trained soldiers and they went about this task in a professional manner, clearing the crowd towards the cathedral, but the damage was done. Within a few minutes at least fifteen people had been killed and over 600 injured. By two o’clock the area was deserted.

Crossing o ver Peter Street we were able to see two more links to the tragedy. A wall at the corner of Southmill Street and Bootle Street surrounds a Friends Meeting House, just as it did in 1819. It was against this wall that one of the crowd was crushed to death as the people tried desperately to escape. Further down Bootle Street is the Sir Ralph Abercrombie, a public house named after a general in the Napoleonic wars. One of the weavers cut down by the Militia was taken here and laid on the bar where he died of his wounds.

ver Peter Street we were able to see two more links to the tragedy. A wall at the corner of Southmill Street and Bootle Street surrounds a Friends Meeting House, just as it did in 1819. It was against this wall that one of the crowd was crushed to death as the people tried desperately to escape. Further down Bootle Street is the Sir Ralph Abercrombie, a public house named after a general in the Napoleonic wars. One of the weavers cut down by the Militia was taken here and laid on the bar where he died of his wounds.

A tragic day, not a day to celebrate you might think. But as Jonathan bade us farewell in Albert Square he made a very pertinent observation. Manchester has been at the centre of some key political movements - the Industrial Revolution, Free Trade, the Anti-Corn Law League, the Co-operative movement, Suffragettes. But these were movements, not moments. It is very rare in history when a particular moment can be singled out as both historic and influential. A bright August day in 1819 was one such moment. 1.45 pm on 16th August at St Peter’s Field, Manchester.

Neil Mullineux

Further resources:

Johnathan Schofield' walking tours etc: http://www.jonathanschofieldtours.com/

A collection of images of documents, and survivors of the massacre: http://flickeflu.com/set/72157627438284420

TimelineTV video: http://timelines.tv/index.php?t=1&e=12

Radio 4 'In Our Time': The Peterloo Massacre: http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p003k9l7

And an excellent site, Spartacus Educational http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/petertm

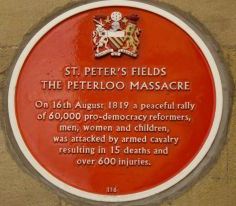

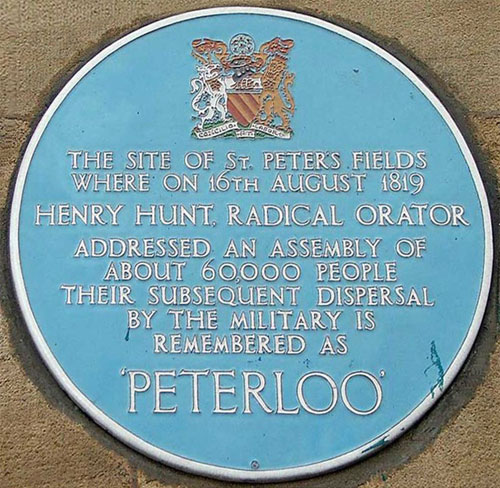

The Free Trade Hall did not exist in 1819. The first hall, a wooden building, was erected in 1840 and this was replaced by a stone building in 1857. However, the site was deliberately chosen because of its link with Peterloo and to demonstrate the link between worker's rights, the Anti-Corn Law League and Free Trade. As such it was appropriate to place a blue plaque on the Free Trade Hall to commemorate the events of Peterloo.

One was placed there by the city council but many people felt that it did not do justice to the event or to the struggle of the people who were killed or injured there.

After a well organised campaign the blue plaque has now been replaced with a red one which gives a more precise description of events on that day.The new plaque is red, not as a symbol of solidarity with the Labour Movement but because that is the colour now used to "..celebrate or commemorate events of importance to the social history of the City..". Blue is for individuals or the building they lived in, and black for buildings of special interest.

However, matters have not ended there. Flushed with success, the plaque protestors are now suggesting that a much more significant memorial should be erected in the area. They are “campaigning for a PROMINENT, EXPLANATORY and RESPECTFUL memorial to this major event in the history of Manchester and its people, and to those who died that day.”

They have set up a website: http://www.peterloomassacre.org/index.html hold regular meetings and ceremonies at the site and have made some headway with the council.

According to the website “Manchester City Council have committed to a new memorial to Peterloo, which will be part of the redevelopment of the St Peter's Square area. The artist's brief is that the memorial should somehow mark other significant Peterloo locations, such as the site of the hustings behind the Free Trade Hall.

No news yet but perhaps all will be revealed when the renovated Town Hall and Library is unveiled.

There is still time for suggestions for an appropriate memorial to be sent to the council.